The Vajrayana Buddhism Experience

Vajrayana Buddhism is considered to be one of the three vehicles that one can abide by in order to achieve enlightenment (the others being Hinayana and Mahayana). Vajra is the symbol of both the thunderbolt and the indestructible material from which it was made (www.religioustolerance.org), and yana is directly translated as being path or vehicle. This is why Vajrayana Buddhism is often referred to as the “indestructible path.” According to their beliefs, it is also said to be the fastest way to achieve Nirvana, which contributes to one of its other names, the “direct path.” This form of the religion has a strong presence in the belief system of Tibetan Buddhism.

I was fortunate enough to attend a Tibetan Buddhist service at the Urgyen Samten Ling, a temple located on the outskirts of downtown Salt Lake City. It was a traditional Puja service, conducted primarily in Tibetan, and provided great insight to the beliefs of those that participated. Through the interpretation of various symbols, rituals, and the means of achieving enlightenment, the practices and beliefs of Vajrayana Buddhism were clearly exemplified during my incredible experience at the Urgyen Samten Ling temple.

A Damaru. Image taken from Exotic India Art.

SYMBOLISM

The presence of symbolism virtually extends to all aspects of Vajrayana Buddhism, particularly those associated with Tibetan Buddhist practices and rituals. From the second I entered the Urgyen Samten Ling Gonpa (Gonpa meaning Temple in Tibetan), though I did not yet know it, I was surrounded by not just various objects, but also things like colors and gestures, all of which bared significance. I spoke with the Householder that led the service, Jay Moreland, about this very topic. When I asked him if the incense represented anything, he chuckled for a

moment, smiled at me, and said, “Tantric Buddhism is full of symbols.” It was not until I asked this question did I begin to understand just how symbolic many aspects of the service were, from the incense to the instruments they used during mantras to the colors of their prayer beads.

Just one of the many examples of symbolism present was the use of the damaru, or hand drum. Often used during recitation of different mantras, this instrument is a small hand-held drum that practitioners will shake back and forth, causing strikers (beads, or the likes, that are attached to the drum by strips of leather) to hit the drum on both sides. The damaru’s purpose is to serve as a channel in which one can send compassion to other sentient beings, and respectively represents compassion and wisdom. On top of all of that, the materials used to make damaru’s, such as various animals skins, woods, and the mantras (written in gold lettering on the inside of the drum), all represent different things in and of themselves. This instrument was used frequently during the service I attended, and almost always accompanied the chanting of different mantras. The way in which the practitioners played the damaru’s seemed very methodical as well as somewhat calming, regardless of the abrupt sound they created.

Another great example of the symbolism present is the use and meanings of colors. From the instant I walked in the door, I was surrounded with bright colors. Pictures of various Buddha’s, monks, or deities adorned the walls, all of which were painted yellow with red trimming. Everything was colorful. Moreland explained that the predominant colors in the service, like red and yellow, were examples of colors that had been blessed by Buddha, but also stressed that any individual color can symbolize a multitude of things. For instance, the color red embodies the energy of life force, but also signifies the delusion of attachment transforming into the wisdom of discernment (www.religiousfacts.com) and is represented by the Buddha Amitabha. These are just a few of the examples that one color can represent and there are five more colors (blue, black, green, yellow, and white) that have deep-rooted meanings.

The symbolism of colors carries over into another significant part of Vajrayana practices and that is the use and meaning of prayer beads, or

Amitabha. Image taken from About.com.

mala’s. Moreland explained that since different colors are associated with different Buddha’s, a practitioner might choose a set of beads with the color of a Buddha they strongly identify with. Like the damaru’s, the materials used to make the beads also represent different things, and likewise, are used for different practices. Of course, aside from all this, their practical purpose is to assist the practitioner in counting mantras. Each set consists on precisely 108 beads, usually made from a type of wood, though mala’s made from materials such as pearls or precious metals are necessary for certain practices. In Vajrayana Buddhism, there are 108 beads so that a practitioner can recite a mantra 100 times, and then an additional 8 to compensate for any mistakes they may have made. I had the opportunity to see this in practice at Urgyen Samten Ling. It required about twenty minutes for them to complete this practice and, at the time, I was baffled or perplexed at what was happening. However, I noticed that all of them had the beads in their left hand as well as a prayer wheel (a tool used to send prayers and energy to other sentient beings in the universe) in their right hand. Unlike the previous hour when they had been reciting mantras as a group, during this period, they each went at their own pace, sometimes resting for a small amount of time before continuing. They recited mantras quietly and, overall, the result resembled humming and created a soothing vibration throughout the room.

The symbolism featured in Vajrayana Buddhism is extensive and these examples are just a miniscule fraction of all that is present throughout their practices. It proves that, like any religion, there is much more than meets the eye and that there is much to be learned about the inner-workings of Tibetan Buddhism.

RITUALS

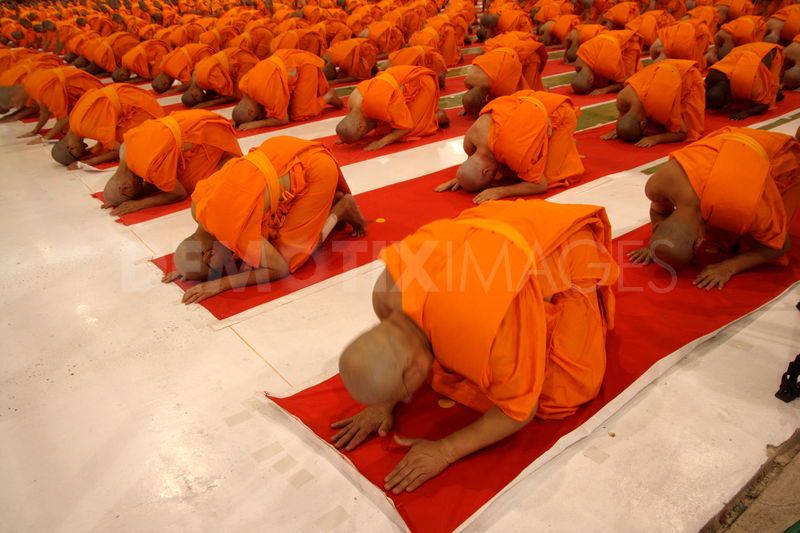

The symbolism present in Vajrayana Buddhism is not limited to just physical objects or sights, but also encompasses many different rituals and their comprised actions. A great demonstration of this is the prostrations that practitioners do. Prostrations are a specific type of bow that represents taking refuge in Buddha, Dharma (the teachings of Buddha) and Sangha (the community), that are together known as the Three Jewels. The service I attended began with one of the practitioners doing several prostrations in front of the statue of Buddha. Prostrations are basically a methodical way of bowing that require touching ones clasped hands to their head, chin, and, finally, their heart as they bow, and correspondingly represent the body, speech, and mind. Moreland described this as “putting yourself below the ideal.” This concept was further explained by Casey Stevenson, a practitioner at Urgyen Samten Ling, saying that prostrations are an act of “surrendering your ignorance to the Buddha for respect and reverence.” I witnessed various practitioners doing prostrations throughout the service in between mantras or whenever they would approach the statue of Buddha, and in some instances, many times in a row.

Prostration. Image taken from Demotix.

Another ritual prevalent in Vajrayana Buddhism is the Renewal of Vows. This is a ritual practitioners do bi-monthly in accordance with the new and full moons. The service I attended was one such ritual. It was lengthier than usual, according to both Moreland and Stevenson, and proved to be a very interesting experience to witness. After they recited the mantra, the Prayer of the Buddha, they renewed their vows to the Buddha as a group. The vows they recited were just a fraction of all of those that exist, but ultimately were called the 14 Vajrayana Precepts (regarding ideal behavior and things one must avoid), the 10 Virtuous Actions (again, regarding ideal behavior), as well as the 18 major Bodhisattva Vows (regarding Bodhisattva practices

and postponing enlightenment for other’s sake). All of these vows are not rules, but rather “practical advice,” as Moreland states, on how to live a virtuous life that leads toward enlightenment. They have a Renewal of Vows ceremony every two weeks in order to remind themselves of their promises and goals, with an aim at correcting any errors they may have made in the recent days.

The extensive symbolism that exists within Vajrayana Buddhism is additionally exemplified through a study of the Puja practice. While I did have the opportunity to experience the Renewal of Vows, the service I attended was also a Puja. These particular services are where the Sangha come together to participate in various practices in an effort to “remove negative hindrances, obscurations, and defilements,” says Stevenson. He further elaborates by saying that each week, they focus is on one of fifteen different sadhana’s, or the means in which one achieves a goal. These are accompanied with specific visualizations of certain deities and their mantras in order to awaken the true nature of compassion and enlightenment that is already present in all sentient beings. This practice is furthered by the utilization of numerous prostrations whilst discarding the five hindrances (desire, anger, laziness, restlessness, and doubt), the Tsog food offerings to the Buddha’s in exchange for their blessings, and finally, calling on the Dharmapalas (or Dharma protector) for security of the teachings and the practice. The service ultimately ends with dedication prayers which dedicate merit and enlightenment qualities to all sentient beings as a means to be freed from suffering and embrace happiness. I witnessed this process in its entirety, as well as the Renewal of Vows. The complete progression took slightly longer than two hours and proved to be incredibly eye-opening. The majority of it was spoken or chanted in Tibetan, but it was quite evident that the practitioners emanated a positive energy throughout the temple and greatly demonstrated just how dedicated to their beliefs they were.

These are just a few examples of the precision of various rituals that Vajrayana Buddhists take part in. Rituals like these require a large amount of practice and knowledge to perform accurately and the meanings of such vary greatly. In the end, however, they all bare meaning towards a similar cause, and that is receiving the Buddha’s blessings through various steps in the process of becoming enlightened.

ENLIGHTENMENT

All aspects of Vajrayana tradition, including the symbols riddled throughout its practices, as well as the various rituals one must partake in, lead down the same path of attaining enlightenment. Every single aspect of these particular practices has significance in the lifelong effort (and many times, multiple lifelong efforts) to become enlightened. One of the first things that Householder Moreland said during my interview was that “everything we see is a manifestation of Buddha.” This includes all human beings. The Vajrayana belief is that the Buddha nature is prevalent in all sentient beings and simply has to be accessed. Of course, this is much easier said than done; nevertheless, with some well-guided assistance and a drive to end the suffering of oneself as well as others’, it is entirely attainable.

Perhaps the most straight-forward guideline of achieving enlightenment is spelled out in the numerous vows that practitioners must make, as well as following the Eightfold Path (the path one must take in which to end suffering.) There are many vows and perfecting them can take a very long time. As a practitioner becomes more and more experienced and higher-ranked, they must take on more and more vows, and thus, following vows becomes more of a challenge. Even masters have confessed to breaking a vow on occasion and Moreland, too, admitted that he himself had broken vows. Of course, the Renewal of Vows ceremony that I experienced exists in order to assist practitioners in reminding them of their vows and of all the things they must accomplish before enlightenment becomes possible. On top of all of the vows, a practitioner must also follow the Eightfold Path, a guideline used to

free oneself from their attachments and desires. These principles are much vaguer than the vows, but they still work towards improving the ethics, mentality, and understanding of each individual.

Another huge contribution to the beliefs of Tibetan Buddhism is that they view enlightenment to be achievable in simply one lifetime, rather than over the course of several. This is not to say that it is easy because both Stevenson and Moreland emphasized that it takes very hard work and unprecedented dedication. This is evident in the translation of Vajrayana (“direct path”), which is also the quickest path to Nirvana. Furthermore, the main goal of Vajrayana practitioners is to help achieve enlightenment so as to teach others the way of doing so themselves. These particular Buddhists

Inside of the Urgyen Samten Ling Gonpa. Image taken from Wordpress.

particular Buddhists swear by the Bodhisattva Vows, a set of guidelines that encourage practitioners to achieve enlightenment, but forego their

own Nirvana. They recite these vows, of

which I witnessed the 18 major vows during the Renewal of Vows ceremony. There are an additional 46 minor vows that

still have great meaning, but are not recited every two weeks. Becoming a Bodhisattva is the intention of being

continually reborn so that they can aid all sentient beings in their own quest

towards enlightenment. Furthermore, this

cycle continues until all sentient beings in all realms have reached Nirvana,

in which case, it is appropriate for Bodhisattvas, too, to become enlightened. One of their main vows, of which I fortunately

heard at the service, was, “May I attain Buddhahood for the benefit of all

sentient beings.” This is their take on

enlightenment in a nutshell and is symbolic of the significant holistic

presence in their beliefs.

There is a reason for the massive amount of symbolism apparent throughout Vajrayana practices and that is because each tool, instrument, color, vow, prostration, mantra and every other element of Buddhism delivers a unique method of connecting with the Buddha. All of these components can be viewed as individual stepping stones that, as a whole, contribute to the “direct path” toward enlightenment.

Overall, the symbolism, rituals, and the means of attaining enlightenment are just some of the demonstrations of Vajrayana Buddhism. Through my experience at the Urgyen Samten Ling Gonpa, I was able to witness these aspects at work in their own environment. My time there offered insight to the beliefs and goals of Tibetan Buddhists and proved that its system of beliefs were much more complex than I had initially anticipated. The Buddhists I had the opportunity of speaking with, both Jay Moreland and Casey Stevenson, reinforced the helpful and holistic nature I had learned were so prevalent in practicing Buddhists. They were still happy to speak with me an hour into our discussion and Stevenson even thanked me for interviewing him, stating that “it helps him go deeper into practice.” I realized in the first five minutes of arriving at the temple that no textbook even comes close to witnessing and taking part in a service first-hand. It was a very powerful and informative experience that left me with a tremendously positive impression and profound respect for the beliefs and practices of Vajrayana Buddhism.